Ernst Koslitsch: Invasion What So Ever

The Invention of the Bomb was the Alien Christ

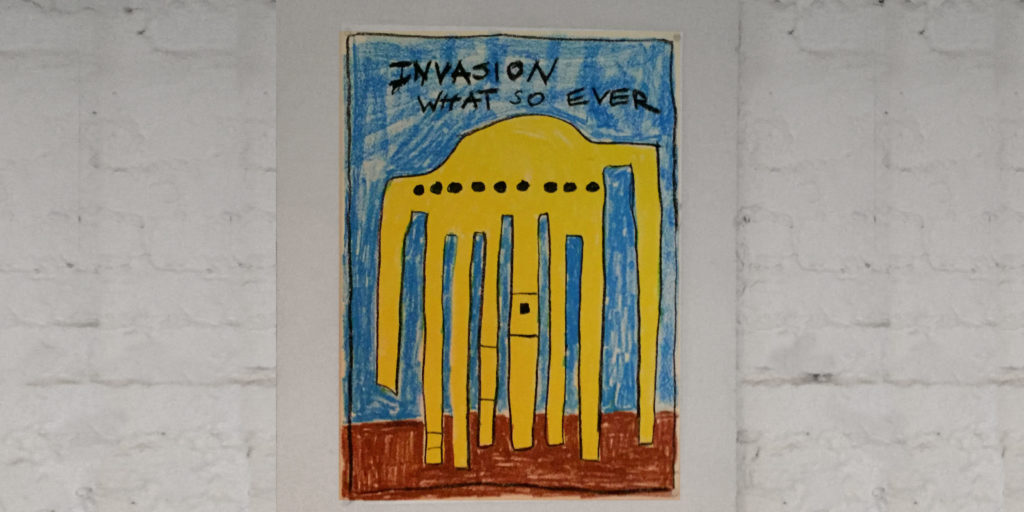

“I want to believe” reads the poster that hangs in Fox Mulder’s office on the 1990s television show The X-files. “Do you believe in UFOs?” is how conversations about contact with extra-terrestrial beings often begin. Viewed as from the sociological standpoint that whether aliens actually exist or not is besides the point, the question of belief informs the fundamental affinities that UFOology culture has with that of Christianity. Aren’t UFOs a kind of a religion?

It is no coincidence that the emergence of contemporary belief-systems around contact with extra-terrestrial civilizations coincides with the atomic bombing of Japan in 1945. As Robert Oppenheimer linked the birth of the bomb with the Hindu god Vishu upon the witnessing the first test test explosion, code-named Trinity, “Now I have become Death, destroyer of worlds.” That liberation of the atom marked humanity’s ascendence to the realm of power previously ascribed as the sole providence of the gods. The subsequent development of world politics into the struggle between Soviets and the Americans was propagandized as a struggle for the ideological survival of the human species with an important difference to all previous world-historical struggles: this time both the loser and the winner would really perish in the ever-lasting fire of nuclear war and the eternal twilight of nuclear winter.

Just as the contours of the nascent Soviet-American struggle were becoming clear, one of the foundational events of UFO culture occurred in Roswell in 1947. In the US state of New Mexico, an extra-terrestrial craft crashed with one or more intact passengers whose existence was covered up by mysterious government agents assisted by the US military which first attempted to cover up the occurrence as not having occurred, and then claimed that the secrecy surrounded the recovery of a crashed military weather balloon.

What if we are alone?

There are strong reasons to believe that we will never contact alien civilizations. If we assume that there is nothing special about humanity, from reasonable assumptions about the values to plug into Drake’s equation, there should be a number of currently active civilization with our local Milky Way galaxy. Fermi’s paradox asks: where are they? Why do we see no evidence of their existence?

Perhaps distances are too great to be overcome. But we should be able to detect the electromagnetic waste emissions of a suitably evolved techne-sphere. Perhaps Earth itself is in a special place: further towards the galactic center there would be exterminating Gamma ray bursts from supernovas. Much further out from the Earth there are not enough metals to support the evolution of life.

Some analog of single cell life itself may be fairly common, as it is on the Earth existing in extreme locations. But multicellular life may be a much rarer occurrence. The Earth has existed for around four and half billion years, with single celled life appearing almost as soon as the initial bombardment of the solar system finished after about a billion years. For three and half billion years, single celled prokaryotic organisms were all that were produced. But they changed the atmosphere, as the present concentration of oxygen was the metabolic byproduct of their cumulative existence. Around 550 million years ago, the Cambrian explosion occurred ushering in the era of rapid and diverse experimentation. As a rough metric during the Cambrian era there were roughly ten times as many different species as any other era in Earth’s history. And what wonderful examples of life there were, monsters with five-fold symmetry, that went extinct without any residual analog in the contemporary biosphere. Why did the Cambrian explosion occur? We have no firm answers, but without it there would probably not have been the cascading contingency of evolution that resulted in us.

Simply having multi-cellular life is perhaps not enough. The dinosaurs existed for hundreds of times longer than humans have, and we have no evidence that they produced a techne-based civilization.

If multi-cellular life is rare, the evolution of the techne sphere is even rarer.

Contact with Aliens will be the Rapture

Of the two possible modes of contact, we may differentiate between the peaceful and the warlike scenarios. To simplify matters somewhat for the purposes of discussion we assume that the aliens are somewhat like us in their manifestation: that they are corporeal beings which make technology by manipulating matter with their appendages, not their minds. That they eat in some manner, consuming matter and energy to

overcome entropy.

New religions always bootstrap their legitimacy via symbolism borrowed from their predecessor. For Joesph Campbell channeling Jung, the social mechanics of archetypes describe UFOs as a new religion brought into being by the existential crisis of nuclear destruction. We created the means to destroy our civilization but are seemingly woefully immature to handle this responsibility. The unfolding events of the last half-century have only served to heighten this unease.

The fictional stories we have created depicting the First Contact with Aliens are even more explicitly clothed in religious symbolism. Aliens are depicted as descending from heaven on pillars of fire. In Steven Spielberg’s “ET: The Extra-Terrestrial”, ET’s touch heals Elliot in the same manner as touching Christ’s robe heals as depicted in Luke 8:40-48.

If aliens form a new secular mythology whose inevitable visitation forms the fabric of a new tapestry of transcendence, then the question of their existence can be seen as analogous to the conflict that a theist faces in her belief in God. If after the confrontation with Nietzsche’s assertion that “God is dead” through a lease of twentieth-century culture, we find echos in the struggles in contemporary Christian society in Europe with substantially declining attendance of actual religious services coupled with ever-increasing insistence that Europe has a Christian culture.

We want to believe that we believe, but the evident decline in church attendance paints a different picture. We find in society the belief that actual belief in Christ as evidenced by daily ritual has declined, and yet we insist upon its supremacy.

If the answer to Nietzsche’s problematic of philosophical existentialism was to find meaning in humanism not religion, to find meaning in human relations, not those with a non-existent supreme being, then perhaps we should start to take the same lesson from the absence of aliens.

Bleak as it might seem to us in these dark days when the beast of fascism once again stalks the West, as atomised as our post-internet society appears in its failure to coalesce around any single nucleus upon which the crystals of meaning may start to form, we ultimately then need to turn inward, to abandon our expectant gaze to the stars, to find the necessary essential ordering of our lives firmly grounded in the uncertain, finite transitory flickering web of human relationships that forms our society.